Lyn Park neighborhood fights to reroute light rail

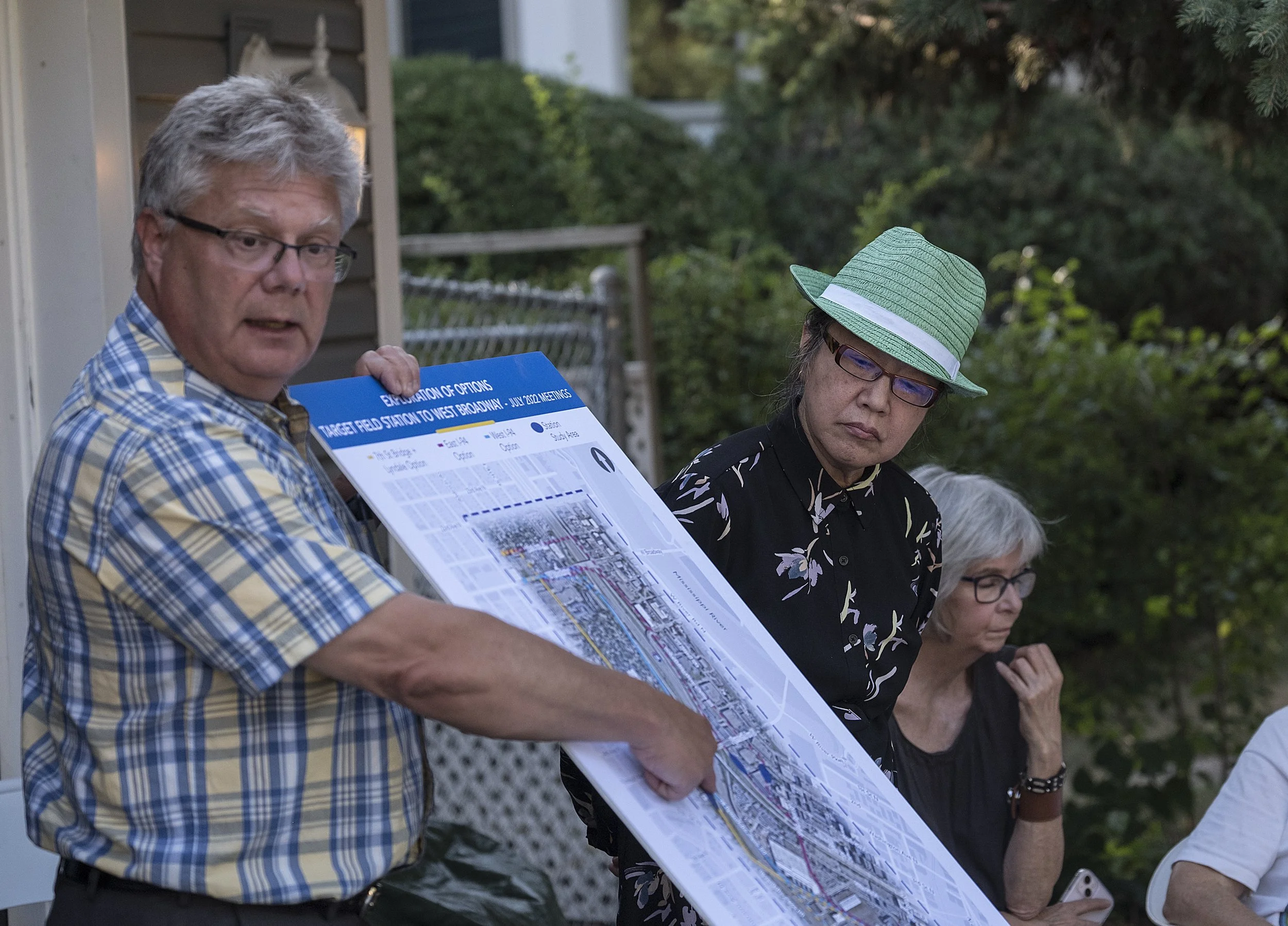

Hennepin County Director of Transit and Mobility Dan Soler tries to assure anxious Lyn Park residents during a driveway meeting in July.

Photos and story by David Pierini, Editor

The cul-de-sacs of Lyn Park, a tucked-away neighborhood in North Minneapolis, were once teaming with children. Shouting and carrying on, they would skip rope, play kickball or shoot endless jump shots into one of those portable basketball hoops. Even as the sun went down, parents had little worry. It was one of those neighborhoods where everybody knows everybody and kept an eye on each other’s kids.

On a recent warm night in July, many of the neighborhood’s kids grown now, a group of residents gathered at the end of one of those cul-de-sacs to challenge transportation officials on a proposal that would bring light rail down Lyndale Avenue and forever change the tranquil blocks that for nearly 40 years seemed impervious to city bustle.

It was a contentious first of three driveway meetings on July 20 that the Metropolitan Council arranged for officials to chat with Lyn Park residents as engineers begin a two-year assessment of the proposed Blue Line extension.

“What are you going to do for the people of Lyn Park when there’s a train winding through a neighborhood that’s 50 years old that was sold to me – I built my house in 1978 – with the idea that Lyn Park is a suburb in the city,” said Bernard Glover. “You’re going to put a train right through it.”

Bernard Glover, who built his home in Lyn Park in 1978, worries the light rail will destroy the tranquility of the neighborhood.

Thousands of decisions will have to be made before construction crews can break ground for track that will connect the downtown to North Minneapolis, Crystal, Robbinsdale and Brooklyn Park. The earliest construction could begin is 2025. But of all the decisions that will bring trains running down West Broadway Avenue, one detail is currently causing great consternation: how to connect Target Field station to West Broadway Avenue.

The current proposal uses Lyndale Avenue, but pressure from Lyn Park residents over the last couple of months has forced officials to consider using Washington Avenue.

In meetings, residents have invoked the word Rondo, the once thriving Black community in St. Paul that was wiped out by the construction of I-94. America is full of Rondos, where mostly Black and Brown communities have been displaced by big transportation projects.

North Minneapolis has seen its share of harm from transit projects. Its two zip codes suffer from respiratory ailments, like asthma, more than other parts of the state because of its proximity to I-94. Both I-94 and the Olson Highway cut the Northside into segments and run through areas that once thrived with homes and businesses.

It is too early to say whether North Minneapolis will have a different story ending as a light rail build comes to West Broadway Avenue. But Lyn Park residents want their say in the narrative.

A sign on Lyn Park Drive references the selling point used to entice people to buy a home in the neighborhood.

A suburb in the city

Lyn Park is bordered by Plymouth Avenue to the South, West Broadway to the North, I-94 on the East and Dupont Avenue on the West.

Lyndale Avenue divides Lyn Park and its roughly 250 residences with two townhouse complexes to the West and the Suburban homes to the East. Crossing busy Lyndale is made safe by pedestrian bridges, used by children over the years to get to any of the three schools nearby.

Residents describe it as an experiment meant to change the image of low-income housing. Following racial unrest in the late 1960s, the city set aside 370 acres of land for redevelopment and granted authority to a group of community leaders to decide what would be built on the vacant land.

The New Franklin-Hall Development Corporation wanted to create a neighborhood with a suburban feel. There was a park, rolling plots of land and the cul-de-sacs more common in an affluent suburb.

Lots were $1,000 and there were five model homes from which to choose. Homes would cost $50,000-$70,000, with the price including carpeting, oak kitchen cabinets, patio doors and a two-car garage. To further attract first-time home buyers, the Greater Metropolitan Minneapolis Housing Authority agreed to cover the closing costs.

Dallas and Barbara Hawes, an interracial couple in their 30s, lived about a mile away. They had been renters for the last eight years and wondered if they could afford to live in Lyn Park. They bought a lot and spent afternoons and evenings visiting the lot.

“We’d come and sit on the lot when it was a pile of dirt,” Barbara Hawes told Minneapolis magazine in 1977. “We’d have picnics here and imagine what it would be like to be homeowners.”

Most of the first residents were either renters or tenants in public housing when they moved to Lyn Park in 1978. Today, it continues to be one of the most ethnically and racially diverse communities in the city.

Some of the original residents, like Glover, remain and whenever a homeowner passes on their home to a grown child, it is celebrated on Facebook as the kind of generational wealth neighborhood planners had hoped for.

Three of its most prominent citizens are Attorney General Keith Ellison, state Sen. Bobby Joe Champion and activist Spike Moss.

Kim Smith’s backyard faces Lyndale Avenue, which is currently part of the proposed Blue Line extension that will bring light rail to North Minneapolis.

“I’ve been here for 32 years,” said Kim Smith, whose driveway hosted the July 20 meeting. “My home is slated to go to my son to inherit. It is the only thing of value I have to pass on to my child.

“This neighborhood is a jewel. This is our little secret, our little piece of the suburbs. It’s amazing how many people have no clue what’s over here. We are not anti-light rail. We are anti-ruining this thriving neighborhood.”

Tight squeeze

Residents insist Lyndale Avenue is too narrow for two sets of tracks and car lanes going in two directions. At 66 feet wide, crews will likely have to cut into the properties. Residents worry their homes will lose value being so close to the track and station.

The back of the homes, where bedrooms are, face Lyndale and residents fear bells and other train sounds will be constant.

Some already living through light rail construction or have been displaced by it warn of transportation officials talking a good game.

Lyn Park residents have gotten to know some of the residents along the Southwest Light Rail project now under construction, who remain furious at Met Council for ignoring their concerns, some of which are now leading to cost overruns.

Two condominium associations say cracks in walls and floors emerged in buildings shortly after construction began on a tunnel in the Cedar Isles neighborhood. Met Council has said it is unlikely construction is to blame for the cracks.

Met Council also dismissed concerns about the route running “dangerously” close to an existing rail line where freight trains carry flammable ethanol, said Mary Pattock, a member of the Cedar-Isles- Dean Neighborhood Association.

Pattock is also upset construction went through and wiped out a 40-acre wooded area along the Kenilworth Corridor, between Cedar Lake and Lake of the Isles, that “was a small forest with birds, fox, deer, turtles. It was nature in the city and they destroyed all of that.”

She has been in touch with Lyn Park residents and has even attended meetings to support them.

“Anybody who lies 500 times, you’re a fool if you believe them on the 501st lie,” Pattock said. “They make a grand show of listening. They check all the boxes, then say, ‘We hear you.’ I could put money on this that (Met Council) will choose Lyndale.”

Why not Washington?

County and Met Council leaders have been diligent in seeking public input on the Blue Line extension. Some have used words like “rigorous and robust” to describe engagement with people living and working in the impacted areas.

They have met with local representatives, business leaders and residents all along the corridor. Met Council scheduled driveway meetings for three Wednesdays in a row in Lyn Park and say they are listening to resident’s concerns.

Their presence at meetings, holding signs that say “Why Not Washington,” has given Met Council some pause and focus time and energy to meet with residents. The three driveway meetings were scheduled for different parts of the neighborhood.

Met Council spokesman Trevor Roy said “we don’t leave anyone in the dark when it comes to designing this thing.” He said engineers are considering all options, not just Lyndale, as they conduct a two- year environmental impact study of both routes.

“I can say honestly that the voices we heard from Lyn Park, have made a difference, will make a difference, on how we analyze getting from Target Field Station to West Broadway,” said Dan Soler, the Director of Transit and Mobility for Hennepin County. “Because of their voices, because of their request, we are adding analysis on Washington. We haven’t taken the Lyndale piece off the table, but public involvement has been heard and we’re going to consider that.”

Eva Cheng gets a closer look at a route map while Soler explains how and why the proposed Blue Line extension was selected for West Broadway Avenue.

Soler has been in the thick of contentious light rail projects for 15 years, holding transit and construction positions with Ramsey County and Met Council.

He didn’t get through his entire presentation on July 20, though he tried. He put his arms out in front him at times as if that would stop the peppering of questions and remarks, all delivered with notes of ire and distrust. His patience was notable and he was still standing at the end, greeting the now familiar faces with warm handshakes and the occasional hug.

Soler told the residents their feedback is already shaping the process but that seemed to do little to ease their minds.

“I don’t expect to try in any way shape or form to change peoples’ fears or concerns because they are real,” Soler said. “But I can say honestly that the voices we heard from in Lyn Park have made a difference and will make a difference into how we analyze how we get from Target Field Station to West Broadway.”

As July came to a close, Met Council had no meetings scheduled with property owners along Washington Avenue.