Displace or Deliver? Northsiders weigh in on whether light rail can fulfill all it promises

Construction of light rail on West Broadway and across Penn Avenue will change the Main Street USA feel of the corridor, critics say. Photo by David Pierini

Story and photos by David Pierini, Editor

A proposed light rail project connecting Brooklyn Park to downtown with a critical stretch in North Minneapolis has its dreamers and detractors.

The dreamers see a significant transportation project bringing unprecedented investment to transform West Broadway Avenue into a destination like Bourbon Street, with restaurants, shopping and entertainment.

Those against the proposed Blue Line extension see another predominantly African American community becoming a casualty to progress. Critics call it Rondo 2.0 as a hark back to the thriving Black neighborhood in Saint Paul wiped out in the 1950s and 60s by the construction of I-94. Critics worry that light rail and the development that follows could quickly gentrify the Northside and price people out of their homes and businesses.

Project planners say they have learned from the past and vow to create a light rail line that serves everyone. They point to hundreds of hours of community engagement, sometimes meeting with people in residential driveways and taking feedback seriously enough to change parts of the route. Officials say minimizing displacement is at the heart of the project.

The proposed Blue Line extension will face critical judgment this fall when municipalities along the line vote on whether to give formal consent to the project.

From Target Field station, a northbound train would travel along North 7th Street, then 10th Avenue, and turn onto Washington Avenue. The train would then crossover I-94 on a new bridge that would extend to 21st Avenue. The train would then merge onto West Broadway Avenue at James.

Should the project receive consent from local governments, construction on the 13.4-mile route could begin within two years, with trains running by 2030. Costs could rise above the current estimate of $3.2 billion.

How the cities will vote is anyone’s guess. Consent is far from guaranteed, and both Northside wards are a no-vote for now.

The Minneapolis City Council will hold a public hearing on Sept. 12 and vote on the consent question on Oct. 2.

Ward 5 Councilman Jeremiah Ellison favors light rail serving his ward but feels the project team needs to offer more details on how they will care for impacted residents and businesses. He wants to slow down the timeline until anti-displacement policies are in place.

“I’m sure the effort they have put in with community engagement feels like more than what they’ve done before, but all that tells me is that the bar was really low,” Ellison said. “I think the way to mitigate concerns about the route is to be rock-solid on how you plan to go forward with anti-displacement.

“You’re rushing a decision that does not have champions at this moment. And they could have champions.”

An informal Blue Line timeline

A light rail plan connecting the northwest suburbs to downtown has been in the works for over 20 years. Hennepin County discussed the idea in the 1980s. It wasn’t until 2012 that transportation officials proposed a route using the median on Olson Memorial Highway to bring light rail to Target Field.

The Blue Line extension would connect the northwest suburbs to downtown Minneapolis. Pictured is a Green Line train pulling into a downtown station.

The route needed the approval of the Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroad, which owned the median’s right of way. Officials tried to negotiate with BNSF to acquire the corridor for light rail. BNSF refused, and Blue Line planners proposed routes down Lowry Avenue or West Broadway in 2020.

Project planners conducted technical studies of both routes and chose West Broadway a year later because the feedback, they said, showed “a strong community preference” for this route.

There was immediate resistance. Residents in the Lyn Park neighborhood opposed a leg of track proposed for Lyndale Avenue. They felt it would disrupt their quiet neighborhood. West Broadway businesses feared they would not survive, much like some small businesses disappeared during the construction of the Green Line on University Avenue in Saint Paul. Community leaders also saw the death of a historic and culturally important corridor that stages block parties and community festivals.

Project planners held community meetings and drive-way sessions, answering questions and fielding a barrage of suggestions. And they listened.

n 2022, Blue Line project manager Dan Soler discussed light rail ideas with residents of the Lyn Park neighborhood.

They removed Lyndale from the map and drew a bridge over I-94 to travel down Washington Avenue for light rail. They also sparred much of West Broadway by drawing the route to travel down 21st Avenue. It is at James that the light rail would join West Broadway. Officials said this change in route would require fewer property acquisitions.

“Minimizing displacement is the lens through which every major decision is made on this project.,” said Blue Line spokesman Kyle Mianulli. “This commitment has shaped the proposed route in substantial ways. (The current proposed route) allowed us to avoid impacting many more properties than if we had stayed on West Broadway.

“We have been in contact with every property identified in these preliminary plans as a potential full acquisition. As planning continues and designs are refined in future phases, staff are always working to find creative ways to reduce and avoid property impacts and continue discussions with property owners.”

As project planners met with neighborhood groups, conducted impact surveys, and designed route and station concepts, an anti-displacement work group met to make policy recommendations for protecting vulnerable businesses and homeowners from construction and steep property tax hikes.

State lawmakers recently allocated $10 million for displacement, and a new Anti-displacement Community Prosperity Board began meeting this summer. Its job is to identify needs and work with governments and organizations to put support in place before the first shovel breaks ground.

Ricardo Perez, a community activist on the new board, is encouraged, saying the steady engagement and commitment to anti-displacement is unprecedented.

Officials could use various tools to mitigate displacement, including housing support like rent freezes, property tax relief, eviction protection, and more intentional construction of affordable housing.

Businesses could get compensation for lost business, relocation costs, and new parking as part of the construction.

Perez believes the small amount put forward by lawmakers may unlock other money for anti-displacement.

“I believe we have enough talent in our network, the community, organizations, and the right government people in the room to forward a different way of building these types of projects,” he said. “We need more than $10 million or $20 million. I think there will be a snowball effect of funding that could come into the corridor. With the right people in the room, we can hyper-focus on the people and businesses who could be disproportionately impacted by the project.”

At recent meetings, more people have come forward to support the proposed Blue Line extension. However, distrust continues throughout the Northside, especially among those working and living along the route.

‘People in limbo’

The North Minneapolis portion of West Broadway Avenue on the route has a Main Street USA feel, especially around the bustling intersection at Penn Avenue. There’s a dance studio, barbershop, the beloved radio station KMOJ, and a modern mixed-use building with Broadway Liquor Outlet at ground level and 103 apartments above.

Owner Dean Rose developed the corner after the 2011 tornado destroyed his business across the intersection. He opened Broadway Liqour in 2016, and his business benefits from some 30,000 vehicles that pass through the intersection daily. Light rail will undoubtedly make it more difficult for cars to turn into his parking lot and change how trucks turn in to deliver inventory.

“When that happens once or twice to a consumer, they’ll go find another place to shop because it’s too inconvenient,” Rose said. “That’s why (bus) is a better option. It’s cheaper, and we can put in more routes that will vastly improve services to North Minneapolis.

“They say that they want to provide great access to everything. But in reality, they just want a means to get people downtown, to the airport and Mall of America. It’s not to actually serve this community but to go through it.”

Andrew McGlory, at a Blue Line update meeting last year, has been critical of the project, saying planners have been opaque on certain details.

Rose and others say they’ve expressed their ideas to project planners but never see their feedback incorporated into route or engineering changes. “They act like they’re listening to us, but they’re not,” he said. “We express ourselves, they have another meeting and come back with less. They never come back with, say, a parking plan. That’s why I stopped going to meetings because they are not considering people in the community.”

Diane Robinson, the owner of Hollywood Studio of Dance, said she had spoken with one project staff member who gave her their card and invited her to call to discuss concerns. Robinson said the person never returned her calls.

She worries about her business surviving the construction period.

“They are looking at the area and doing these surveys, but they don’t care because they don’t live here,” Robinson said.

The Blue Line must acquire the Five Points Building, home to KMOJ radio, which recently signed a long-term lease extension. KMOJ board president Dr. David Hamlar said the station has had discussions with project planners, who have said they will work with KMOJ to move to a new location on the Northside.

KMOJ has used public service announcements to attract citizens’ participation in Blue Line hearings or written calls for feedback.

“They are listening,” Hamlar said of the project team. “But it has been a little bit slow. If they want to engage us (Northsiders), they need to put us on a front burner and not be reactionary.”

Teto Wilson, who owns Wilson’s Image Barbers and Stylists on 2126 West Broadway, still opposes the light rail plan but has shifted energy into working with anti-displacement leaders for potential compensation should construction hurt his business.

Barber Teto Wilson, who owns a shop on West Broadway near Penn Avenue, says he has switched his energy from opposing the project to being compensated for lost business during construction.

“If certain things are done properly and they put measures in place to make sure we are able to survive, then we’ll be fine,” he said. “Hypothetically, if they say the rules are the rules and you have to figure it out for yourself, then we may not survive.

“There are just so many unknowns, and it’s kind of leaving a lot of people in limbo.”

Dreamers say, ‘Why not?’

Mike Tate, a youth coach at North Commons Park for 46 years, wrote a heartfelt letter to transportation officials supporting the Blue Line.

In it, he wrote about losing one of his players to gun violence and was present on Plymouth Avenue in 1967 when racial tensions flared and fire destroyed some blocks.

“This is not about a train or stops or even buildings,” he wrote. “(This) is about opportunity and hope for our young people and an opportunity to overcome so many demons our community has suffered since the mid-60s.”

A recent bus tour of the proposed Blue Line extension route passed by signs opposing the light rail project.

On a recent Saturday, project manager Dan Soler led a bus tour of the route connecting Brooklyn Park, Crystal, Robbinsdale, and North Minneapolis with downtown. The crowd was small and Blue Line-friendly.

He is calm and affable when he stands in front of a room full of critics and explains why the proposed Blue Line light rail extension route is good for them.

Before boarding a Metro Transit bus at UROC on Plymouth Avenue for the tour, Soler appealed to the group by leading them in a chorus of “why not?” Take the mural of musicians that greet motorists turning onto Broadway from I-94. It provides a perfect gateway to a destination, he said.

“Why not another Bourbon Street? Why not another Beale Street?” Soler said of the two iconic centers of American culture and commerce in New Orleans and Memphis, Tenn.

Dancers from Nuestra Lucha MN perform on a closed off section of West Broadway Avenue during an August health fair.

Among those boarding the bus that morning were a realtor, a developer, and a businessman from Albertville. Hennepin County Commissioner Irene Fernando, whose district represents the Northside, joined the bus tour near the end to provide rousing support for the project.

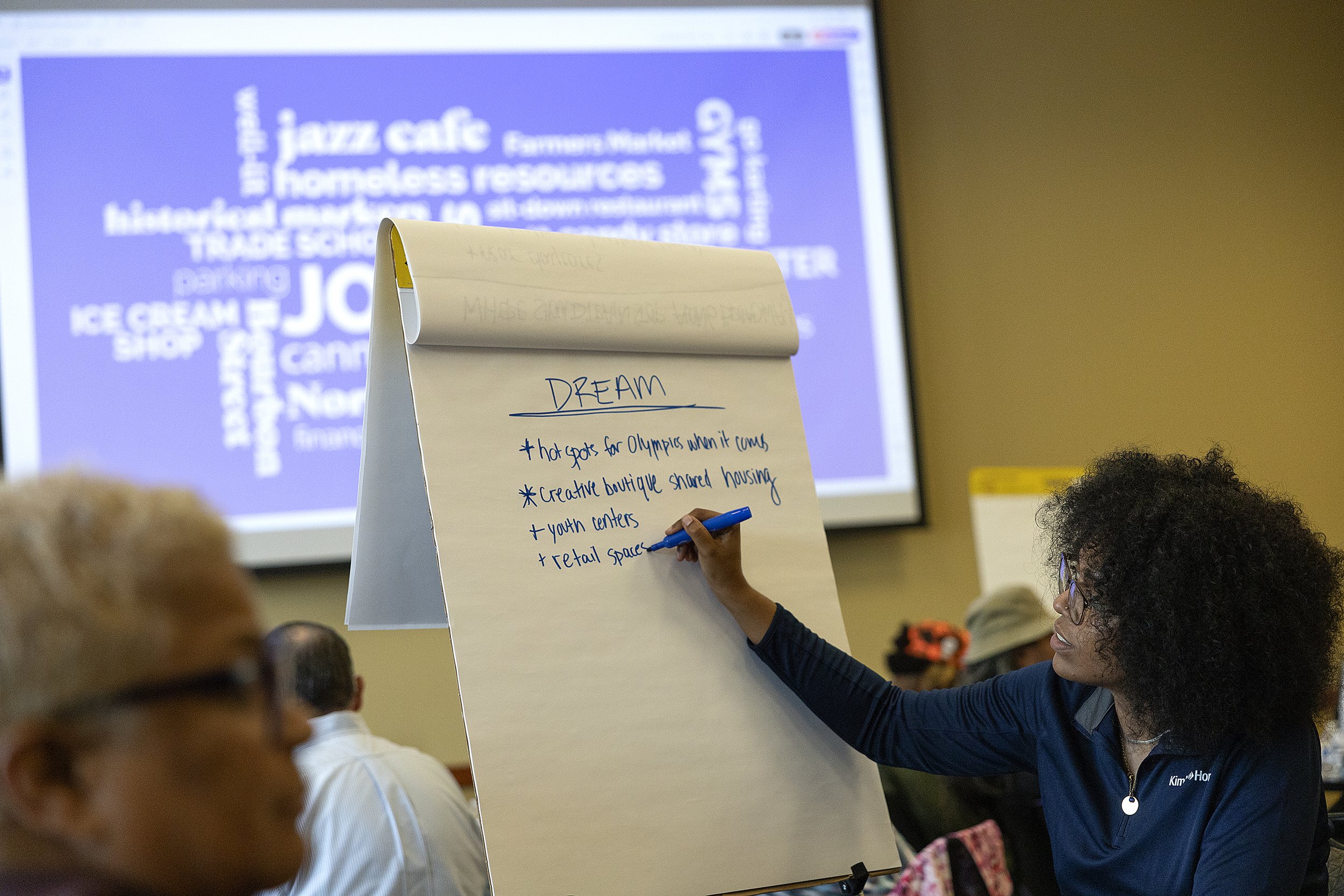

The bus tour was part of a series of four “Dream” sessions led by Northsider Brett Buckner, director of OneMN. Buckner’s team designed sessions to unite people and share ideas on what they want light rail to bring to the community.

“The thing about West Broadway is there are so many opportunities, and we are the last to be developed,” Buckner said. “This is our moment.”

Blue Line supporters at a recent meeting offered ideas of what they would want from a North Minneapolis transformed by light rail.

At a recent meeting that invited residents to dream of what light rail could mean for North Minneapolis, two attendees viewed the route online to check proposed station locations.

John Jamison, who chairs the Northside Resident Redevelopment Council board, said Blue Line proponents need to communicate better the benefits of having light rail in North Minneapolis.

He said some Northsiders are skeptical because they are not used to a process that asks them to deliver feedback to help a good plan evolve.

“They need to know they can write this new chapter,” Jamison said. “Instead of saying the county is doing this to us, we can change that position to say they’re doing this for us.”

The bus stopped at the Capri Theater so that Fernando, dressed in her “Commish” baseball jersey, could join the last part of the tour.

She took the microphone Soler used to guide the tour to generate excitement about light rail. Critics accuse Fernando of avoiding contentious meetings with residents.

“For too long, government has pre-negotiated your vision,” said Fernando, who chairs the county board. “We can look at each parcel of land and not limit ourselves to the ideas of the past. Every resident of the Northside should be able to age here, get jobs here, buy cool stuff here, and have our hard-earned money stay here. I look forward to the transformation that is possible here.”

Project planners used a wall at the Capri Theater to bring a closer view of every part of the proposed route.