Opioids: a growing crisis

As overdoses and heroin use seem to be increasing on the Northside, response efforts are also ramping up.

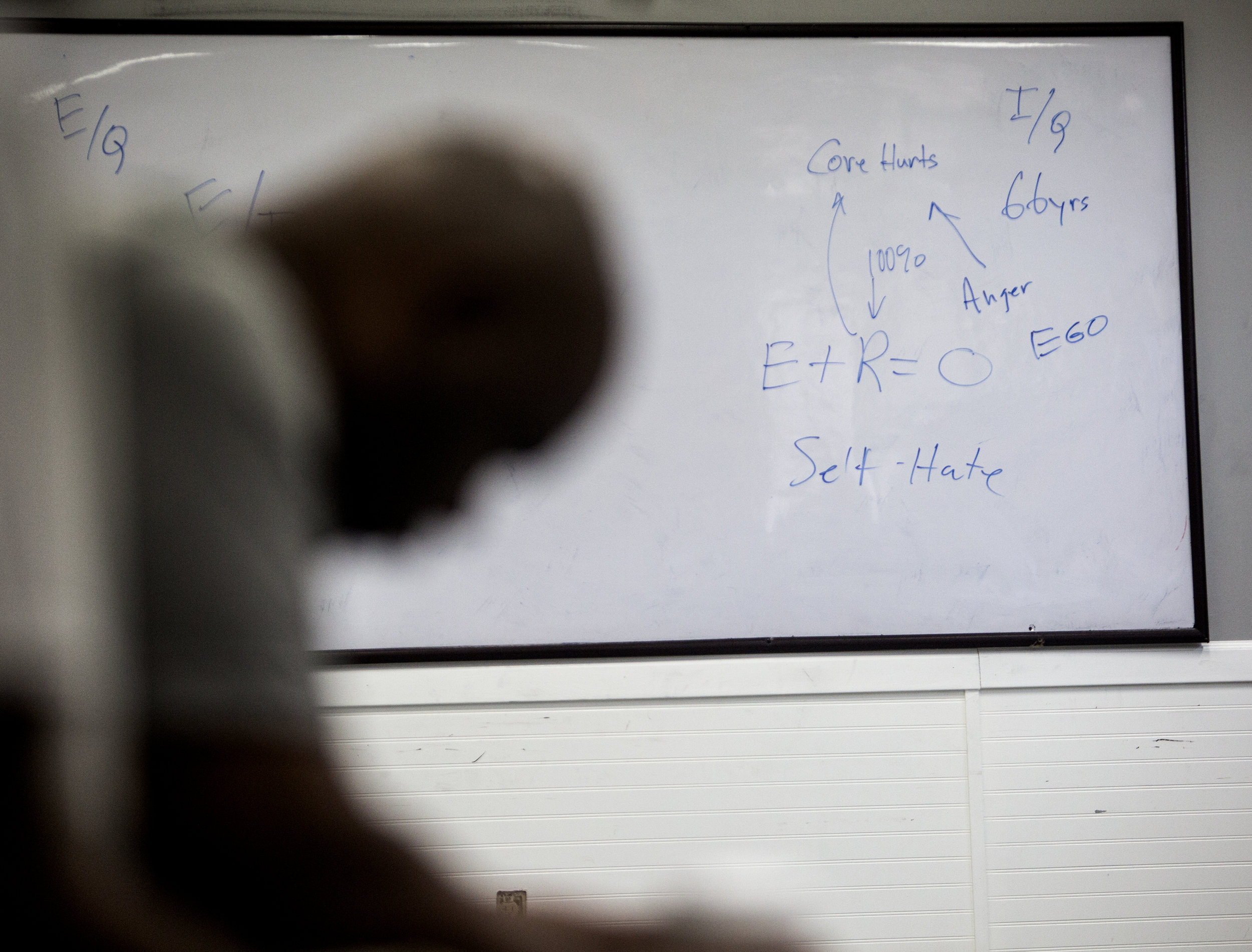

A recovery meeting at Turning Point focuses on some of the issues fueling addiction. Photo by David Pierini

This story is part of a series on how the opioid crisis has hit the Northside that ran in the 9/27 print edition of North News.

By Kenzie O'Keefe Editor

Today, as opioid manufacturers are facing large-scale lawsuits, the destruction caused by their drugs is just beginning to be addressed in North Minneapolis.

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 12 this year, the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) received 154 overdose calls for service from the Fourth Precinct, concentrated particularly on W Broadway Ave. between Lyndale and Emerson. The citywide hotspot for calls are the northern Phillips neighborhoods, where 189 calls were received.

Noya Woodrich, Deputy Commissioner for the Minneapolis Health Department, says those numbers likely underestimate the problem for opioid overdoses. “We’re fairly sure that for every overdose we hear about, there are two others we don’t hear about,” she said.

Despite data showing that African Americans, Indigenous people, and youth are disproportionately affected by opioid abuse, nationwide media narratives frequently depict the epidemic as a predominantly white, rural and suburban crisis.

“It’s an equal opportunity problem,” said Woodrich, adding that there is no profile of a typical user.

This is not the first large-scale drug epidemic to hit the Northside community. The ramifications of the crack cocaine crisis of the 80s and 90s are still felt today. Poverty, racism, lack of opportunity, and other social determinants of health have made pain management an essential part of survival for generations of Northsiders. For many, coping with trauma has meant descending into addiction.

Here in Minneapolis, narratives about opioid abuse—and the resources that result from them—seem to focus more heavily on South Minneapolis where the crisis is most pronounced, but not restricted. Anecdotes from community members and public officials suggest that the epidemic is growing on the Northside.

According to MPD data analyst Rachel Crews, the majority of Northside opioid overdoses seem to involve “diverted prescription pills,” particularly oxycodone. This year however, there's been an uptick in overdoses involving heroin. “Overdoses from intravenous heroin were very uncommon in the 4th Precinct until around mid-April of this year,” she said in an email to North News on Aug. 27.

Noya Woodrich says this reflects an overall trend of the crisis: “pill problems will eventually turn into heroin problems.”

Old Highland Neighborhood Association President and social worker Angelina McDowell says her neighbors are being impacted. “I’ve heard so many stories at our neighborhood meetings about people finding dirty works in our alleys and our parks,” she said. “It’s frustrating and it’s sad.”

Hawthorne Neighborhood Council Executive Director Diana Hawkins says her organization is responding to substance abuse and all the dysfunction it creates in the community. Though she tackles many types of chemical dependency, she’s especially concerned about opioids. She says she’s heard stories about young people bringing pills to schools. “A lot of kids start using opiates because somewhere in their life was trauma,” she said.

Hawkins is concerned about legally obtained prescription pills too, explaining that two of her neighbors died of fentanyl overdoses this year. “You have to be careful, even with a legitimate prescription. They took too much and passed,” she said.

Northside medical providers say the number of patients they’re seeing with opioid use disorders is increasing. Dr. Brendan Cullinan, a family physician at NorthPoint, estimates that about 10% of the patients he sees during his work days struggle with opioids.

Anthoni McMorris, part of A Mother’s Love street outreach team, says he is seeing more open drug use on Northside streets, particularly West Broadway. He says he sees business owners closing their bathrooms off to public use due to fear of overdoses taking place there.

McMorris says he sees the general public “overlooking” drug use and “acting like nothing is happening.” He fears this will lead to “people dying on the street.”

HARM REDUCTION AND HEALING

The causes of widespread opioid dependency and addiction are diverse and multi-faceted, and so, say officials and those suffering, must be the solutions.

“We can’t criminalize this to death. We can’t arrest this away,” said Angelina McDowell, who hopes Northsiders will “come together as a community to show some community, to show some compassion,” and respond in “person-centered” and “harm-reducing” ways. She would like to see a mobile needle exchange program implemented in the community, particularly near Merwin Liquors on W Broadway Ave.

Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey’s Multi-Jurisdictional Taskforce on Opioids released its recommendations for combating the crisis in August after a year of meeting in subcommittees of relevant stakeholders. The recommendations stressed the need for culturally specific response efforts tailored to individual communities.

“The culturally specific education and treatment and community outreach is going to look different in North Minneapolis and South Minneapolis because the needs are different and the community network is different,” said Heidi Ritchie, policy director for the Mayor.

Making naloxone (often referred to by its brand name “Narcan”) more widely available is one top priority for city and Hennepin County leaders, whose first responders, including county library security personnel, all carry the lifesaving, overdose-reversing drug (pictured on the cover of this paper).

Ensuring communities have resources that are effective available to them, like medically assisted treatment, is another priority.

Medically assisted treatment appears to be one of the most effective ways to control an opioid addiction long term. NorthPoint Health & Wellness located at Penn and Plymouth Ave. N has employed a full-time Suboxone coordinator, Jeni Klotz, for over a year now thanks to federal grant money intended to combat the opioid crisis. Suboxone is a mild opioid offered to patients by licensed providers as a way to manage their long term, chronic illness: addiction.

“We’re also giving them other services, helping them get better,” said Zadok Nampala, a senior social worker at NorthPoint. “It’s more holistic. They’re not getting it out on the streets. They’re getting it with some education behind it. They can have a more fulfilling life in community.”

Julie Bauch, Hennepin County’s Opioid Response Coordinator has been tasked with implementing the county’s Opioid Response Strategic Framework, released in early 2018. She says making medically assisted treatment accessible to those caught up in the criminal justice system at the county jail and workhouse is vital. “It means people who come to jail or the workhouse will be assessed for an opioid use disorder, started on medically assisted treatment like Suboxone if required, and they will be connected to a community clinic upon their discharge for ongoing care,” she said. According to county data, 40% of the total jail population is incarcerated related to opioid use.

But harm reduction approaches can be challenging to implement, as in the case of pharmacists. Community pharmacists have the legal authority to sell syringes to people without a prescription. While clean needles can prevent the spread of Hepatitis C or HIV, selling syringes to opioid users can also result in an overdose. One pharmacist who asked not to be named described this “catch-22” as very hard: “I don’t think I received any training in school that prepared me for these types of dilemmas, choosing between the spread of disease or possible overdoses.” Pharmacists are also challenged when they refuse to dispense syringes as they are often accused of discrimination or profiling.

When it comes to supporting people in recovery, Diana Hawkins from the Hawthorne Neighborhood Council says love, compassion, and second chances are often missing. “There are plenty of resources out there. Honestly, people that are struggling, from what I see, what they need is TLC. They need someone who will trust them and give them a chance. …I have people saying ‘I can’t get a job because of my situation,’” she said.

NorthPoint's Nampala would like to see more resources to combat homelessness (a major barrier to recovery) along with a more connected network of Northside organizations who provide opioid addiction resources. “Here we are competing for clients and not having the best outcomes. If we could find a way to work as a team, that would be my dream come true,” he said.

Emotional support is a large component of Jeni Klotz’s role at NorthPoint. She says people come to NorthPoint feeling “ashamed.”

“One of the things that I do and I think we all do is really validate that nobody start out wanting to be an addict. Life happens and there are consequences,” said Klotz. “I just say ‘I’m so glad you’re here.’”